A very short book now, to get me back into the swing of things, since I’ve been so lax about reading and posting. I was recommended this without a huge amount of blurb, so didn’t entirely know what I was being handed. And to some extent, I’m glad of that, because unexpected books can be some of the best books. And it was interesting all on its own too, of course.

A very short book now, to get me back into the swing of things, since I’ve been so lax about reading and posting. I was recommended this without a huge amount of blurb, so didn’t entirely know what I was being handed. And to some extent, I’m glad of that, because unexpected books can be some of the best books. And it was interesting all on its own too, of course.

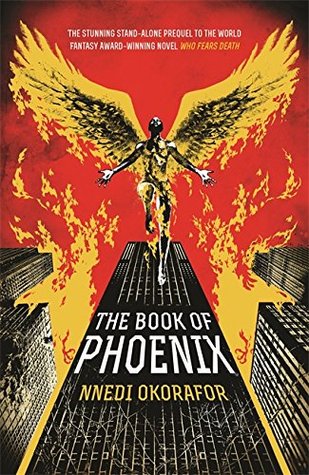

The Book of Phoenix is a sort of prequel, sort of not (the author calls it a sister book) to Who Fears Death, a story of a girl with powers in a post-apocalyptic future Africa. I haven’t read this, but was aware of it before I read The Book of Phoenix, and so had some amount of context to connect the two. I doubt it was necessary, but it was interesting, and I think it may help when I (soon) get around to reading Who Fears Death.

The Book of Phoenix follows a woman who was created to be more than human, then kept locked up as a science experiment in a tower block full of fellow test subjects in New York, in a grim, semi-realistic near future. Technology has leapt ahead, as has global warming, but the world is not a happy one, and there are a lot of problems. Phoenix is only two years old but has the body of a mature woman in her forties. She has never left her tower. We follow her as a dramatic event changes how she thinks about the place she’s lived her whole life and her relationship with people and the world around her. It’s a combination of a coming of age story, a grim near future SF and something else that’s kind of just itself.

One of the things I actually found quite so interesting about the book is that fact that Phoenix is so chronologically young. She’s been given access to books and information, and has grown at an accelerated rate, but there are moments when there does seem to be a naivety about her that can only come from having just two years of lived experience – and a restricted, trapped and guided two years at that. This partially comes through in her speech and actions, but I think is most prominently visible in the way the story is narrated and structured, because the narrative bookending of it is that it is Phoenix herself telling her story to someone in the distant future, via a recorded speech saved on a computer. And the way the story flows follows both the meandering way that stories told orally often do, but also a… not childishness, because Phoenix is anything but, but an immaturity of some aspects of her relation with the world that betray her in her storytelling. I spent a lot of the book unsure how deliberate this was as a decision, but when I got to the end, I was pretty damn sure the author had been rather clever about it all. This naivety makes Phoenix a surprisingly compelling character to read – I’d have expected the reverse – especially when combined with the emotional depth she has in other directions. Her perception of herself is complex and developed, while her her view of the world is hampered, and it leads to a richness and irrationality of characterisation that really does make her feel… well… real.

But, because the story is presented as something she’s telling orally, this has a sort of downside, in that the presentation, pacing and direction of the narrative form part of her characterisation, and suffer slightly for this. One of the things I struggled with for most of the book was trying to decide whether this was a deliberate choice and part of that characterisation, or just slightly iffy story-telling – I came down firmly on “deliberate and successful choice” by the time I got to the end, but it does mean that the flow of the story is… a little odd. It does very much feel like the flow of a story told by a normal person – it takes turns in odd places, because it’s about how they think and feel about the things that happened to them, not how a story ought best to be constructed. You get asides, and information presented not quite at the point you’d expect it. It mostly works, I can see what she’s doing, and it really does feed into giving us a sense of Phoenix as a person… but I didn’t fully enjoy it as it did detract from the coherence of the storytelling.

The book is also really rather short, and this leaves you with the feeling of a lot of different threads and ideas being set up – really interesting ones that I want to know more about – but then never being resolved, or not resolved fully, because there just wasn’t enough space. It makes me keener to read Who Fears Death, because I imagine some of them will get picked up there, but it left an amount of dissatisfaction when putting the book down – that feeling of “but what about…?”.

That being said, it’s still a story I had no difficulty throwing myself into, and I didn’t really want to put the book down as I was reading. For all that I have some qualms with the construction, the heart of the story is a good one, and one told in a slightly unusual but mostly successful way, with characters I care about and, in the case of the main character, have a complex self that doesn’t pin itself just to a particular trope. Phoenix isn’t totally sure who she is herself, and that exploration is really interesting, and does work to make a character you both care about and want to read more of.

There’s one other thing that makes this book both compelling and frankly just good for me, and it’s something that bleeds through on every single page… and something I should probably read more of, truth be told. On top of everything else happening, all the other emotions going on through each character and each thread and each event, there is a constant, present and palpable sense of anger, sometimes visceral, seething and violent, sometimes quieter and resentful, but always there, and much of the time right up front and centre.

Nearly everyone in this story is either from Africa themselves, or with a recent African descent or (since some characters have been genetically constructed) a strong DNA link. And many of them have been taken directly from Africa, many in their childhood, to the US, denied any sort of autonomy, even bodily autonomy, and been treated as less than human. There’s even, in the science tower, treated much the same as all the other “experiments”, a group of monkeys. The message being sent there is not a subtle one. But it’s slightly more complex than that – the scientist we have a name and a face for is also from Africa, born in Nigeria and come to the US, hoping that the work she does in the tower will get her her citizenship. I don’t think at any point we have a named white character (or if we do, the fact I can’t remember them suggests they’re not exactly important*), though some exist in the periphery, more concept than person, driving what goes on behind the scenes to create the circumstances of the story. And so you have these two themes – the one about the dehumanisation of Africans, with explicit, spoken links to the slave trade within the novel, and then the one about the complexity of oppression, where Bumi, the Nigerian scientist, is part of the machinery of oppression and dehumanisation (with no remorse or complexity given on her own part – she fully supports what she’s doing and pursues it with zeal – but with an unspoken complexity that assumes that her fervour comes from the position she has been put in by her situation, and her need for US citizenship).

I think this, in many ways, is the most successful part of the book (as well as the characterisation of Phoenix herself, but the two go very closely hand in hand). It brings a raw emotionality to the story that… I don’t think I’ve encountered in many places, but it’s a raw emotionality overlaid with a cold, hard determination. This is not emotion the irrational, this is emotion that drives action, and it really really works in terms of how it sets the tone for every action. Because I said sometimes Phoenix’s story telling took odd turns? Part of this is that she takes actions that don’t seem, initially, to make a huge amount of sense. But in the context of that all-driving anger, in the context of a woman suffering hugely and with the power to push back against that, her actions make so, so much sense, and that I think is what Okorafor does so well – she embraces emotional rationale ahead of necessarily detached logic, and so everything just feels… so much more real. Because that’s how people really do think.

That all being said, the book as a whole fell into a tricky gap for me in terms of rating. It’s one of those ones where I see and appreciate what it’s doing, and know it’s good… but also don’t think it’s massively for me? I enjoyed it, but not with the mad passion I enjoyed say… All the Birds in the Sky, or Ninefox Gambit. I think, had it been a longer book, that would have changed, but the unresolved threads niggle at me a lot, and I want to know what happens to so many people and things that I can’t settle. And so for me, it’s in the gap between three and four stars on Goodreads, with the potential to sit solidly in four if, when I read Who Fears Death, I get some resolution on those. Because I know this one was written second, so I can’t totally blame it for not filling me in on context that would have already existed if I’d read them in the other order. That being said, the more I reflect on it, the higher the rating I want to give it, so this may change in a week or so without any outside help anyway. Opinions are weird.

Next up, I should try to finish The Vorrh, but I may abandon it for the huge stack of other things threatening to fall off my desk. We’ll see.

*The only white characters I can recall, and I don’t think they are actually named, are a group of men who come to a village in Ghana and are generally self-important and awful about the place until stuff happens. It’s a bit more than that, but spoilers. They’re not fleshed out people, they’re villains, and rightly so. There’s a lot of not-at-all-subtle colonialist echoing going on in that bit of the book, and it is absolutely deliberate about the lack of subtlety. Which… really works well within the tone of the rest of the book.

Pingback: Who Fears Death – Nnedi Okorafor | A Reader of Else